In the 50s and 60s, people would blindly send their poetry or lyrics, $50, and receive a 7” single of their work turned into a finished song. A professional singer would “sing” the words as best he could in one take, and session musicians would play along, template-style. The genre was mostly country and western, but studios turned out pop records.

These mail-order song shops turned out tunes quicker than Berry Gordy did at Motown, but they did it with none of the passion or commitment to creating a work of art.

There was no one name for these records, but they were sometimes called personalized records, custom singles, your own record, or even vanity records. There’s a documentary movie called Off the Charts: The Song-Poem Story, which claims ‘it’s estimated that over 200,000 song-poems have been recorded since 1900’, so let’s go with Song-Poem.

Song-Poem Records: An Early Iteration of AI!

I was recently reminded of Song-Poem records when a friend shared a video of Mark E. Smith’s record collection. Mr. Smith had a notorious Song-Poem record in his collection, and that sparked an epiphany-ah.

Song-Poem records and large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT operate the same way – people provide half-baked or even loony ideas, feed the machine (be it human or digital), and in return they get results ranging from dreadful to meh. Neither Song-Poem records nor AI require real talent, yet both can make anyone an artist, an expert, or just about anything one could dream of. In theory, anyway.

Naturally, I turned to AI to research this lost phenomenon of trading fifty bucks of hard-earned cash for a vinyl copy of your words put to music. My adventure was fun, so I created this blog.

I had AI write the story of Song-Poems in the style of an Alan Cross radio show/article.

If you live outside of Canada, chances are you have never heard of Alan Cross. But he’s been on Toronto radio for as long, or longer, than Mark E. Smith fronted The Fall1, and he’s syndicated across Canada, including one show called The Ongoing History of New Music. Cross kind of takes an AI approach to his radio programs, gathering research and then reading his findings in a hokey yet ever-so-earnest voice.

Check out Alan Cross’ website, A Journal of Musical Things, if you want to get a better understanding of what his work is all about.

(And the bot did a pretty good job of emulating Mr. Cross, too!)

DISCLOSURE: The rest of this post is AI-Generated.

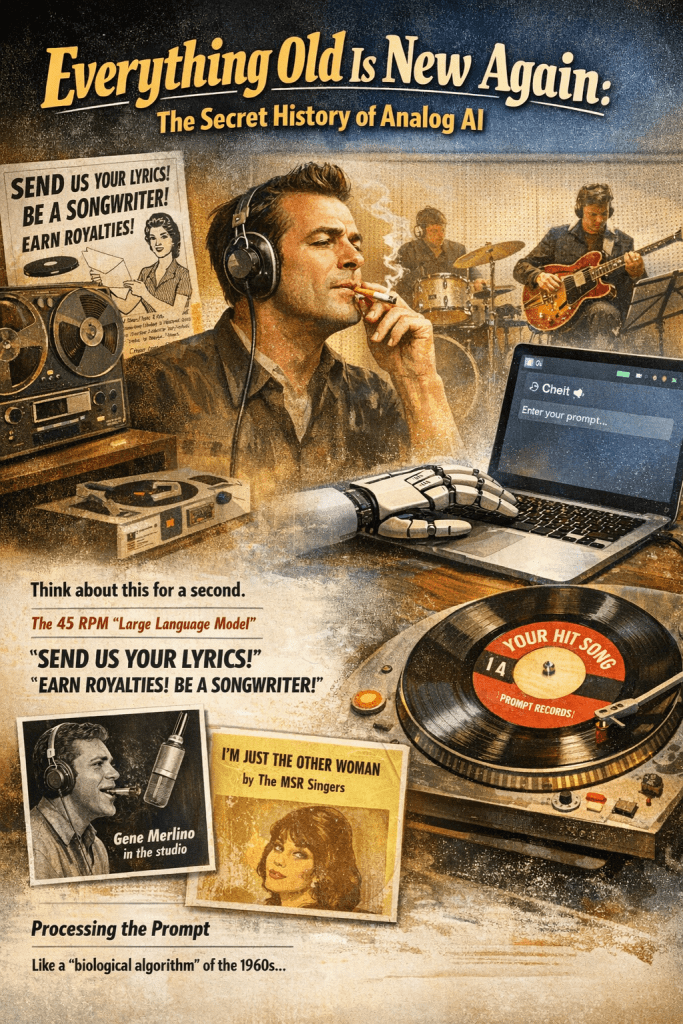

Everything Old Is New Again: The Secret History of Analog AI

Think about this for a second.

We’re told that we are living through a “revolution.” That Artificial Intelligence—the LLMs, the deepfakes, the algorithmic pop stars—is a brand-new, world-shaking disruption. We’re told that for the first time in history, you can type a few lines into a box, pay a small fee, and a “machine” will spit out a polished, professional piece of art.

But what if I told you we’ve been doing this since the Eisenhower administration?

The fact is, the “prompt-to-product” pipeline wasn’t invented in Silicon Valley. It was perfected in wood-paneled “bedroom studios” in the 1960s. And back then, the “black box” wasn’t a cluster of GPUs—it was a group of cigarette-smoking session musicians in Nashville.

Here is the story of the Song-Poem.

The 45 RPM “Large Language Model”

In the 50s and 60s, you’d see these ads in the back of Popular Mechanics or comic books. “SEND US YOUR LYRICS!” they’d scream. “EARN ROYALTIES! BE A SONGWRITER!”

All you had to do was mail in your poem—about your cat, your heartbreak, or your weird theory about the government—along with about fifty bucks (around $500 in today’s money).

A few weeks later, a 45 RPM record would arrive at your door. It sounded… well, it sounded like a real record. It had the correct tempo, the correct chords, and a professional-sounding singer.

But here’s the thing: The musicians didn’t care about your lyrics. They didn’t even know you. They were essentially a biological algorithm.

Processing the Prompt

And the Song-Poem workflow was a lot like modern AI. You sent in a prompt (your lyrics), then a pre-trained model (the session musicians’ with knowledge of 12-bar blues and pop structures) then performed inference (mapping your weird words onto a standard melody) and gives you an output ( the record).

The “stars” of this world—guys like Rodd Keith or Gene Merlino—were the human equivalent of a high-end processor. Merlino claimed to have sung on over 10,000 of these songs. He’d walk into the booth, see lyrics he’d never read before, and sing them perfectly on the first take.

He wasn’t “creating” in the traditional sense; he was generating.

The Hallucination Effect

Just like ChatGPT can “hallucinate” and give you weird, confidently wrong information, these song-poem records were full of musical “glitches.” Because the musicians were working at such high speeds—sometimes recording 50 songs in a single afternoon—they didn’t fix mistakes. If your lyrics were clunky or didn’t rhyme, the singer would just “force” the rhythm, creating a bizarre, uncanny-valley version of a pop song. It sounded almost right, but just “off” enough to be eerie.

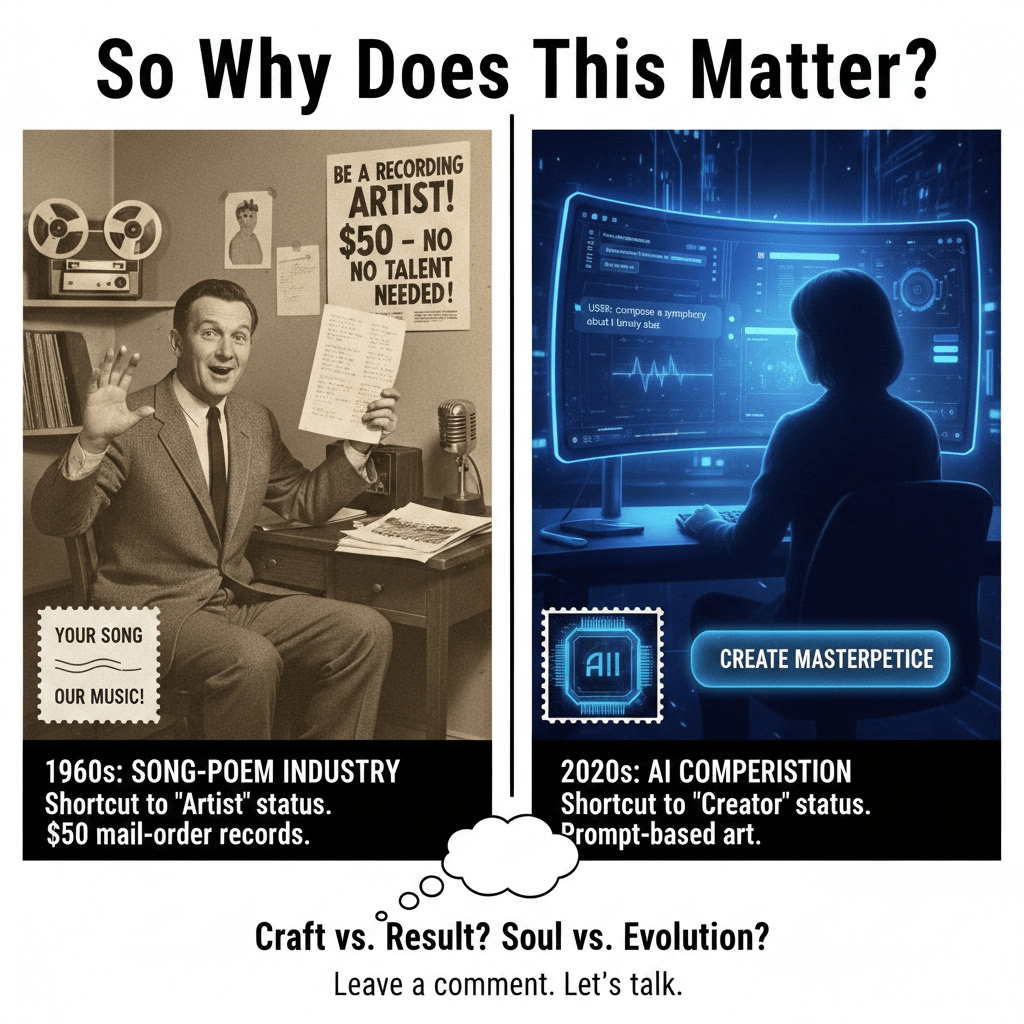

So Why Does This Matter?

IIt matters because it proves that humans have always loved the shortcut. Let’s be honest: we are wired to take the easy way out. Historically, if you wanted to be a recording artist, you had to put in the “10,000 hours.” You had to learn an instrument, find a band that didn’t hate each other, and practice until your fingers bled.

The Song-Poem industry changed the gatekeeping. It allowed people without a lick of musical talent, people who couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket, to bypass the hard work and jump straight to the “Artist” phase. For fifty bucks, you weren’t just a guy with a notepad; you were a “Recording Artist.”

Does that sound familiar?

It’s exactly what AI is doing right now. It is the ultimate democratization—or, depending on how cynical you’re feeling today, the ultimate dilution. AI lets us do things we aren’t actually qualified to do. You don’t need to understand color theory to “paint” a masterpiece, and you don’t need to know a C-major from a G-seventh to “compose” a symphony.

We’ve traded the craft for the result. The interface has changed from a postage stamp to a chat window, but the ghost in the machine—that deep-seated desire to be “creative” without doing the heavy lifting—is exactly the same.

What do you think? Is AI just the high-tech version of a $50 mail-order record? Are we losing the soul of the craft, or is this just the next logical step in musical evolution?

Leave a comment. Let’s talk.

The Playlist: Artifacts of Analog AI

If you want to hear what this “Analog AI” sounded like, you need to dig into the archives. Some of it is genuinely catchy; most of it is a fever dream of mid-century clichés.

- “Blind Man’s Penis” (John Trubee): The gold standard. Trubee sent in the most absurd, offensive lyrics he could write just to see if a studio would record them. They did—and it became a cult classic.

- “I’m Just the Other Woman” (The MSR Singers): A bizarrely nonchalant take on infidelity, sung by a session group that sounds like they’re reading a grocery list.

- “Human Breakdown of Absurdity” (Norm Burns): A sprawling, weirdly profound track that feels like an AI trying to write a philosophy thesis about a car crash.

- “I Lost My Girl to an Argentinean Cowboy”: Proof that the “prompts” of the 60s were just as weird and unpredictable as anything you’ll find on Reddit today.

- A total of 66 different musicians played in the English post-punk band The Fall during its 40-year existence from 1976 until the death of frontman Mark E. Smith in 2018.

Mark E. Smith was the only constant member throughout the band’s history. The lineup was famous for its frequent changes, leading Smith to once quip, “If it’s me and your granny on bongos, it’s The Fall”. About one-third of the members who joined the band played for less than a year. ↩︎

Leave a comment