Below is the story told entirely from the POV of the snowflake civilizations, a chorus of microscopic societies living and dying in the space of a fall—observing Constance Pryor, CEO, from their crystalline vantage point. The tone is mythic, surreal, and darkly whimsical. They see themselves as ancient beings, though each one lives for less than a second.

“THE FALLING KINGDOMS”

A Snowflake-Civilization POV Story

We are born in the high vaults of the cloud-temples, carved from vapor and chill, named by the lightning that flickers silently in the mist. Each of us is an empire. Six-sided, six-spirited, six-storied. We emerge complete: crystalline nations built in an instant by the breath of winter.

Our world begins with the first trembling downward.

The Fall.

We do not fear The Fall. The Fall is our time. The Fall is all time. We live more fully in these seconds than larger creatures do in decades. They take time for granted. We are time—brief, bright, fractal.

We look upon the vast world below with curiosity. The giants who walk it seem trapped in slowness—tragic, lumbering beings who age while we glide.

One of these giants watches us now.

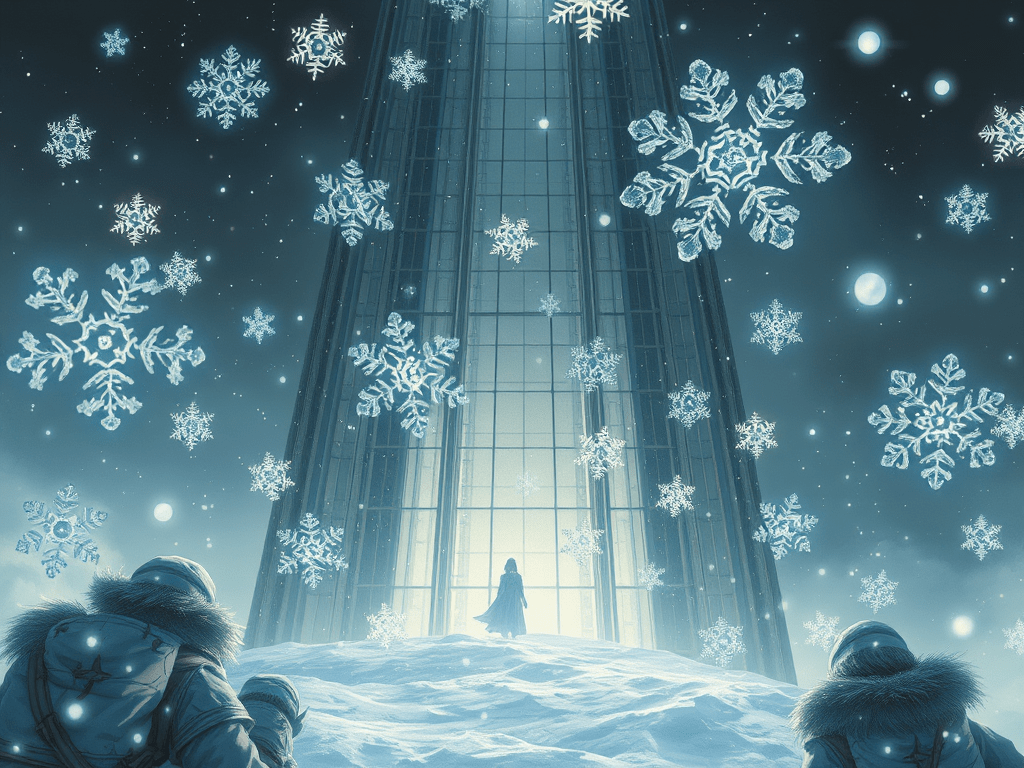

The Woman of the Glass Tower.

We know her. All snow-kingdoms know her. Her window is a common landing field, though few of us survive long after touching it. She is a somber sentinel, a queen of steel and silence, wrapped in heavy fabrics and heavier grief.

Our elders whisper that her eyes used to blaze like the sun before she mislaid her heart somewhere in her towering fortress. They say the shadows around her now are self-woven.

We watch her as she watches us.

Her gaze is frantic today, a tremor in her soul-light. Even from here—tumbling through open sky—we feel it. Her mind radiates like overcharged static.

“Behold,” say our Councilors, their crystal voices chiming through our lattice halls.

“The Giant Queen unravels.”

We spiral closer.

Around us, the younger snow-realms cheer. We are entering the Viewing Path—the sacred trajectory that leads past the Glass Tower. It is an honor to be seen by a giant at all. It gives our brief lives meaning.

We are not the first to pass her window on this day. Many empires have already ended upon her ledge, their histories melting into her building’s cold stone. But each flake has its own destiny.

We rotate, revealing our sunward facet. It is considered polite.

The Woman presses her fingertips to the glass. We feel the pulse of her heat through the barrier—monstrous warmth, enough to annihilate us instantly. We hold formation. We do not flinch.

A hush spreads across our crystalline corridors.

“She communes,” someone whispers.

Indeed, her eyes meet ours—wide, glassy, desperate. The kind of stare one gives to omens. The kind of stare that asks questions no snowflake should answer.

“What does she seek?” ask the newborns, their kingdoms barely complete.

“She seeks sense,” reply the elders. “It has slipped from her grasp like a thawing flake.”

Below, the Glass Tower’s halls echo faintly. We hear her machines murmuring, her staff speaking in muffled tones. The Giant Queen ignores them.

She watches us as if only snow can explain the world.

In truth, we have seen her deterioration over many storms. At first she wore her power tightly, like armor that never creaked. Now it sags around her, a costume she no longer fits.

The rumors among us say her mate left her. That a soot-covered trickster has claimed the mate’s heart instead. We do not understand the giants’ marital rituals—they seem unnecessarily complicated—but we sense the wound in her.

It radiates visible light.

The Fall continues. Our time grows thin.

Across our crystalline plazas, citizens gather for The Final Assembly. It is tradition: recounting our entire history—from birth to dissolving future—before we strike the Earth or the Window or the Unyielding Sidewalk.

The Speaker ascends the dais.

“We have lived well,” he proclaims. “We were born. We glimmered. We sensed the sorrow of a giant. These are the great achievements.”

But we are not done.

A gust of wind shifts us, flinging us sideways, closer—much closer—to the Giant Queen’s window. Her breath fogs the glass. We pass inches from her eyes.

In that instant, we see inside her.

We do not mean metaphorically.

We mean inside—deep within the labyrinth of her unraveling mind.

Her thoughts swirl like chaotic weather:

- Beanbag chairs of impossible proportions

- Marshmallows worshipped as pastel gods

- Fractals that whisper advice

- A creeping fear that the HVAC vents are sighing judgment

- And the overwhelming dread that she is more melt than ice now

We glimpse these things and mourn for her.

“We must leave her a message,” declare the elders.

“But she will not hear us,” say the young.

“We will leave it anyway.”

As we descend past her window, our facets adjusting to catch the light, we angle our crowns to reflect a single beam directly into her eye.

A glint. A pulse. A tiny flicker of truth.

Our message is simple:

You are falling too, but you may yet land gently.

And then—

The Ledge.

The End.

Our world collapses into droplets, our nations dissolving into a tiny sheen of water that streaks the edge of her building. Our histories rush back into the cycle of vapor and sky.

But before consciousness leaves us entirely, we feel it:

She saw the glint.

She understood something—maybe not all of it, but enough.

As our final awareness melts away, we hear her whisper through the glass:

“Everything ends. Even storms.”

We approve.

A good ending, for a giant.